Letter to Diognetus

On the seemingly collective rejection of God and the philosophies of René Girard.

No. 139: Letter to Diognetus

I

You’ve probably noticed of late I’ve focused a lot on Christianity, Christian doctrine, and Christian thought. If so, you are correct. Over the last six months, I’ve been deeply interested in the ideas, principles, and truths I’ve discovered in the texts and teachings of Christianity, especially those found within the intellectual tradition of the Catholic church and its fathers, the only establishment next to its sister Orthodox church that can be linked in an unbroken chain to the life and times of that enigmatic man par excellence, Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ, the Son of God.

And why shouldn’t I take a deep and earnest look into these matters? Apparently my heart and mind were thirsting, and I found drink. Like many today, my own ignorance or the ignorance of the culture made me bereft of these teachings. I hadn’t been properly invited nor invited myself to take a good and honest look at what might be there, and this seems a common oversight in a world that has perhaps over-confidently—and certainly depressingly—proclaimed with Nietzsche that “God is dead. And we have killed him.”

It takes only a moment to look around and see that if you don’t go searching, you won’t stumble upon the ideas and truths that moved mankind from inception to now. This is the failure of our milieu. Nowhere in media or culture will we encounter ideas that challenge the material and social status quo. Even in art this is becoming increasingly rare. A quick example can be found in a popular book of revisionist history that recasts Joan of Arc as a non-religious, feminist badass, when in fact everything this great and deeply religious heroin (and saint) accomplished was attributed, by her, to God. When world-shaping ideas go absent in such a way, it seems not only right to start asking questions, but our burden to do so.

Only today do we find nearly a whole society of people who believe they have things right and all of human history had things wrong. Only today do we find a society that believes modern science is at odds with all the truths revealed in the history of mankind, and since the utmost reverence must be paid to science, all previous revelations are made null and void. Take a society that’s so proud of itself as to severe its ties to thousands of years of human history and predict where it might end up. I am no prophet, but the signs are there. See: pervasive loneliness, increasing suicide rates (at lower ages), absence of morality, death of the arts, etc.

This is, in some ways, not new, only different. Even Nietzsche lamented the collective decision to forget God with the warning, “When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet. This morality is by no means self-evident… Christianity is a system, a whole view of things thought out together. By breaking one main concept out of it, the faith in God, one breaks the whole.” And what immediately followed in Nietzche’s era was the fallout and atrocities of two world wars.

What jaw-dropping arrogance! Is it not? And if this seems too-harsh a condemnation, let’s explore why it’s not. Is it fair to shout arrogance at a society willing to presume that the 99% of humans who have ever lived and believed in God are contemptible, and the 1% is correct? Chances are, yes. I’m no better, however. I’ve come to this POV because it’s played out in technicolor throughout my life, and along the way, I hope, I’ve become more aware.

When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet. This morality is by no means self-evident… Christianity is a system, a whole view of things thought out together. By breaking one main concept out of it, the faith in God, one breaks the whole.

To prove it, let’s take a brief look at my history, which may look something like yours.

I was born in the San Francisco Bay Area, grew up there, and went to public school there. I was baptized in the Catholic church and my parents sent me to Catholic catechism as a child, confirmation, etc., but to be quite honest, it didn’t really register, and the passion was never fully there—which I imagine is the case for many young children whose parents, trying to do the right thing but being probably unsure of things themselves, send their kids off to church with fingers crossed.

After this, a regular and secular and Godless lifestyle proceeded. My parents allowed this, to their credit, for forcing the issue is never the way. I went to a big university. I believed in the goodness of humanity as the means and the end. I went along with what I was taught, pushing the boundaries but never daring to peek outside the box. I became a good acolyte: a supporter of abortion, an intellectual vs. a religious, a reader of the Communist Manifesto. Never during this journey was I radically challenged with an alternative viewpoint. Never did anyone in academia, or the culture, or in the arts or media, seem to challenge me to seek a transcendent point of view. Rather, all seemed perfectly happy with a consumerist, materialist understanding. And never did I allow my mind to go to potentially sacred places in the traditional sense, for if I happened to be challenged, being so indoctrinated and ultimately afraid of what I might find, I recoiled.

In my moral vacuum, I was in fact a good boy according to the American intellectual standard. Thankfully, however, by some grace, I always maintained some sense of depth, of soul, of heart, of truth, of mind. I maintained some individuality and independence of thought. And I despised any of the ways fear attempted to limit my freedom to pursue a gut feel. I can’t say where these tendencies came from—from my parents, maybe, or from my reading; maybe even from that catechism; maybe, if I might approach her awesomeness, from God, like Joan of Arc—but they tinged everything in that morally ambiguous world with a sense of absurdity. Worse, a sheepishness. If in history universities were places for free thought, today they are the most Orwellian environments imaginable. Thus, through the events of life and reading and writing and all that unconsciously bear us on to new patterns of thought, I decided to explore—or rather, return to—the source of my skepticism at the food I was being fed. I could try to permit certain thoughts and actions my university peers would approve of, but the underlying sense of shame and dirtiness was there like a pebble in my shoe, or a voice that kept whispering: You are above this. You were not made to live in this way.

II

A great contradiction reigns today: a people who, to their credit, believe in goodness and progress and science and each other and “a better world,” but who do not believe in God.

Is this possible? Real question.

It seems that without God—whatever that word might mean to you—all is meaningless. Without God, there is no good or bad. Without God, there is no reason to encourage progress or expend any energy to that end. Without God, there is no art. Without God, there is nothing true but only subjective relativism. Without God, love is only an evolutionary instinct. Without God, there is simply no difference in being alive or dead. If any or all of these truth claims scandalize you as they scandalized me, you may have some thinking to do. In this sense I wonder if I haven’t always been a believer in God, only that I’ve called God by lesser names. I came close to the top of the mountain, but didn’t have the courage to reach—or even attempt to reach—the summit. And though the following concept is not all-encompassing, it could have been so easy: in the story of Moses, God names himself, saying, “I AM”. Surely this is one simple yet great attribute of God, that attribute we all share—along with all the earth and the cosmos—in merely existing.

This brings to, what I think is, the hardest part: the humility required in admitting we do not know everything, but do believe and hope. A great humility is required in plunging a sword into our modern-made pride and facing the fact that we may be curious about God, and so more like those we’ve criticized, or mocked, or belittled than we’d gladly admit. There’s great humility in not placing the blame for our lame curiosity—for there are many, many bad people who spout the word God, and many ridiculous ones, too—and instead putting the onus on ourselves to do our own research and come to our own understanding, stripping away the noise and discovering the bare naked story for ourselves. There is great humility, too, in working with a text in earnest, since all of the Bible and other religious texts were written with human hands “inspired by God,” meaning we must read with a literary mind appropriate to the genre (and the bBible contains many books and many genres). Finally, there is great humility in complete and utter submission, which pretty much follows by default after recognizing that, oh, perhaps humanity itself is not the beginning and the end of the story, but part of it, like the musicians of an orchestra.

For me, this humility was made easier after realizing the transcendent is not at odds with science in any way, which is the common narrative pushed today (because when the culture or media does bring up religion, it’s to vilify). In fact, the first scientists were religious men and women. After all, why practice science unless there is some truth be uncovered? If all were mere chaos, science would not exist. But all is not pure chaos. There is an intelligible order. Why? These discoveries and more begin to unravel for those who seek, such as the story of Abraham (you have a destiny which will present itself to you—and you can seize the day or recoil from it—and if you seize it, the world will open up for you and your descendants—and if you don’t, you miss chance) or the story of Isaac (even when facing the scariest challenges—which may involve you giving up everything—go forth courageously with the trust that things will work out—and they will). This takes effort, however, and we need not harp on the ever-increasing rareness of that golden stuff.

These thoughts and more might lead one, as they lead me, to re-investigate ideas of God (and, in my case and moment, the ideas of Christianity) at a more critical and mature level. Given the world’s tendency to ignore the religiosity of the people, structures, and institutions that made our world, and given our modern teachers’, pundits’, and intelligentsias’ sly way of skipping past any chapter that may include mention of God, I’ve become curious about the religion—not the flawed practitioners of it—at the foundation of the civilized world from 50 AD (AD = “Anno Domini” or “the year of the lord”) to, let us generously say, 1930 AD.

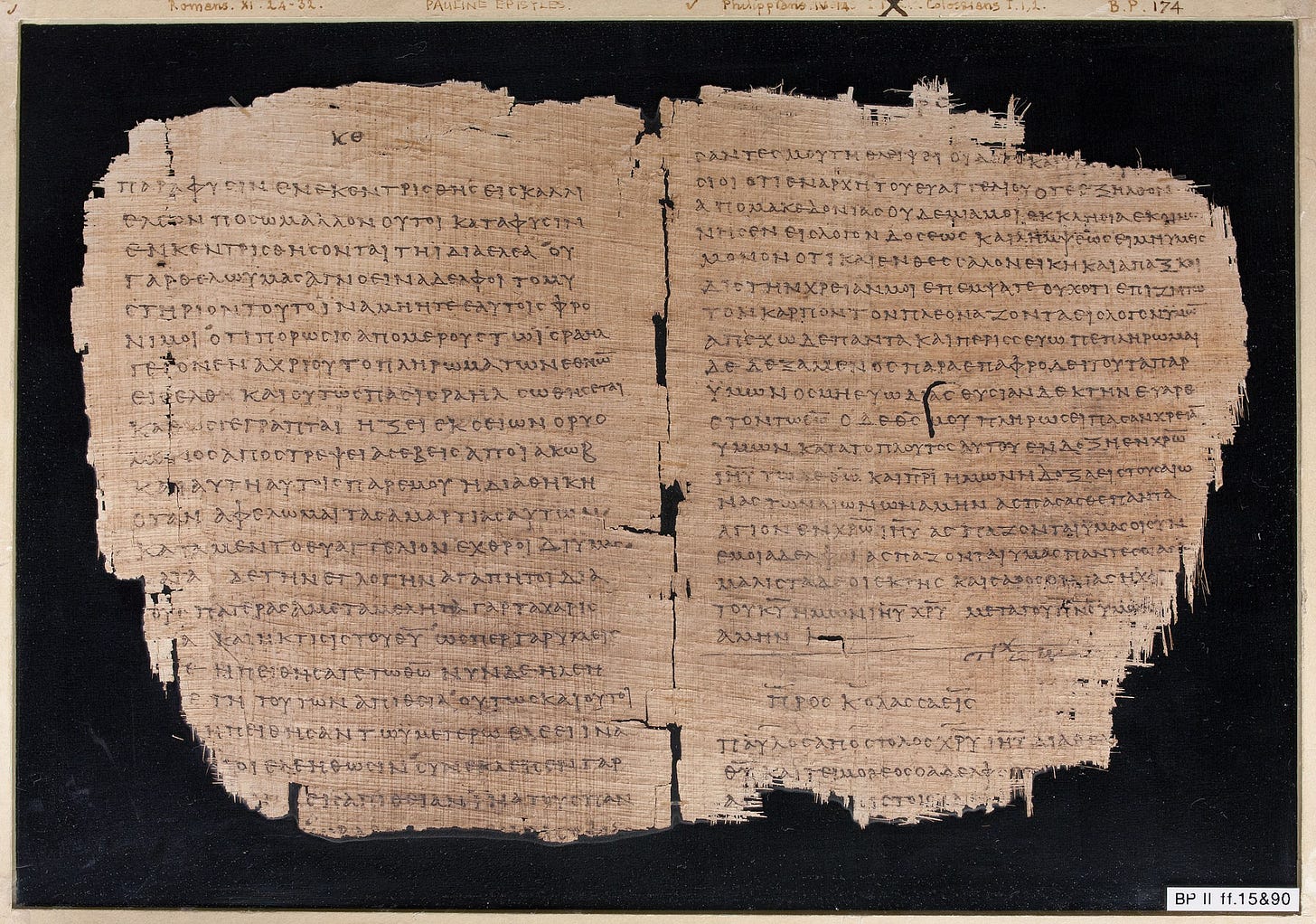

And to be sure, there’s a lot. But if you’re willing, let’s take a quick look at a particularly beautiful text called “Letter to Diognetus,” written in Greek by an unknown author sometime between 125 AD and 200 AD to a pagan audience. It serves as a kind of explainer letting pagans know who Christians were, what they believed, and why they were different.

Here’s an excerpt, with some callouts from yours truly between:

The difference between Christians and the rest of men is neither in country, nor in language, nor in customs. They dwell in their own fatherlands, but as temporary inhabitants. They take part in all things as citizens, while enduring hardships as foreigners. Every foreign place is their fatherland, and every fatherland to them is a foreign place. Like all others, they marry and beget children; but they do not expose their offspring. Their board they set for all, but not their bed. Their lot is cast in the flesh; but they do not live for the flesh. They pass their time on earth; but their citizenship is in heaven. They obey the established laws, and in their private lives they surpass the laws.

In other words, these are a people who, unlike their contemporaries, are more than just the citizens of a state, but human beings and, as such, sacred. They have children, but protect them from slavery, sex work, and pagan ideology. They give their food, their drink, their money to those in need, but do not sleep around and do not swap their wives and husbands for sex. They are material beings, but live for matters of the soul as well. They obey the laws, but finding even these lacking, surpass them in their good deeds, self-control, and willingness to forgive, for mercy will never be found in the law of man.

They love all men; and by all they are persecuted. They are unknown, and they are condemned. They are put to death, and they gain life. They are poor, but they make many rich; they are destitute, but have an abundance in everything. They are dishonored, and in their dishonor they are made glorious. They are defamed, but they are vindicated. They are reviled, and they bless; they are insulted, and they pay homage. When they do good, they are punished as evil-doers. They are made war upon as foreigners by the Jews, and they are persecuted by the Greeks; and yet, those who hate them are at a loss to state the cause of their hostility.

Above all, they are loving, for they believe God is love. They are persecuted because of their love, which may sound surprising, but isn’t, because the evil person, when presented with love and forgiveness instead of revenge, sees more clearly their own evil and despises the forgiver the more. They are poor materially, but have everything in terms of love, community, family, friends, and all that truly matters. They pray for their enemies.

To put it briefly, what the soul is in the body, that the Christians are in the world. The soul is spread through all parts of the body, and Christians through all the cities of the world. The soul dwells in the body, but it is not of the body; and Christians dwell in the world, though they are not of the world. The soul is invisible, but it is sheathed in a visible body. Christians are seen, for the are in the world; but their religion remains invisible.

In incredible poetic form, here the writer makes an analogy that lives in my brain: the way the soul lives invisibly in our bodies, so God lives in us and in every aspect of the material world.

Finally, the letter delivers the reason these Christians have come to such an understanding: one God in three persons, or, the Trinity.

It was truly the almighty, all-creating, and invisible God himself who established among men the Truth from heaven and the holy and incomprehensible Word, and set Him firmly in their hearts. Nor did he do this, contrary to what one might suppose, by sending men to some minister [...] or one of those in charge of earthly things [...] No, He sent the very Designer and Creator of the universe Himself, through whom He had made the heavens, and by whom He had enclosed the sea within its own bounds; whose mysteries all the elements of nature faithfully guard; from whom the sun received the schedule of its daily flight; whose command the moon obeys in lighting up the night; to whom the stars give heed in following the path of the moon; by whom all things were ordered and bounded and placed in subjection.

But did He send him, as one might suppose, in despotism and fear and terror? Not so. Rather, in gentleness and meekness He sent Him, as a king sending a son. He sent Him for saving and persuading, not for compelling. Compulsion, you see, is not an attribute of God.

Indeed, before Christ came, what man had any knowledge at all of what God is? [..] Oh, the magnitude of the kindness and love which God has for man! He did not hate us nor reject us, nor yet remember our evils. Rather, he was long-suffering, and He was patient with us. In His mercy He Himself took up our sins and He Himself gave his own Son as a ransom for us, the holy for the wicked, the innocent for the guilty, the just for the unjust, the incorruptible for the corruptible, and the immortal for the mortal.

With that treatise fresh in our heads, let’s ask: with what aspect of this do we take issue? Where do we find fault? What is the ratio, let’s say, on first glance, of truth to falsehood? Of word and intent that is truly good vs. selfish, hateful, and bad? At the very least, was more harm done by reading this Text Which Shan’t Be Published, or good?

It seems safe to say that goodness, truth, and beauty are things we should follow with all our hearts, and as shown in the first half of this excerpt, this is the Christian doctrine. Where should we take issue with a life dedicated to following, participating in, and appreciating the good, the true, the beautiful? Might we already be doing this?

Thus, again, this is only a small example, but I can’t help but wonder and wonder again: Why are such texts scorned by the culture? Barring the all-too-common reproach that religious people have done bad things and assuming that they live virtuously and according to the actual teaching (which is surely the norm if not useful for gorey histories), why?

One obvious reason may be due to what’s covered in the second paragraph: that a doctrine so full of love scandalizes those who would rather not measure themselves by that standard. For example, the man pursuing great wealth to buy cool things; or the talk show host, whose job it is to basically talk shit about people who can’t defend themselves; these cannot abide by such a contract. As alluded to in my last newsletter, these call for either a radical or partial shift in how we live, and a shift in our hearts and minds, and we respond with thanks but no thanks—a hesitancy, which I respectfully posit, can only stem from fear.

The latter half of the letter, I imagine, is where most of modernity’s agnostics and atheists will take issue.

Sure, they might say, I permit God. But this talk about the Son, etc.? It’s incredulous.

I get that. I would add, though. Shouldn’t it be? We cannot expect talk of God to be casual, matter-of-fact, or easily-grasped, can we? This should rack our minds. This should confuse. This should be immensely difficult, as the ideas discussed here are surely beyond comprehensive understanding, being from God. This is perhaps where too many judge the concept of religion by its practitioners, who may often behave as if an event as mind-blowing as God becoming man and defeating death is just, like, pretty much normal.

Certainly, it’s not. The idea of God cannot, and should not, be casually slurped down like an ICEE on a summer’s day. Given those other two aspects of a religion, though—faith and hope—inroads can be made, and let us not forget that tough one we talked about earlier: humility.

On this, I’ll leave you with one more thought, one that helps me begin to make sense of what Jesus Christ is. It comes from one of our fellow creatures rather than the Creator himself, making it slightly less mind-blowing: a French philosopher by the name of René Girard. The short of it is this (please read Girard if you’re interested, because my summary is bound to fall short):

III

Girard developed an idea called Mimetic Theory. Essentially, he posits that human tendency is to mimic each other, namely in our desires. Thus, what another person wants, we want, for the sole purpose that the other person wants it.

Stay with me.

Usually it’s those we admire whose desires we mimic. This can be seen everywhere. Look at those pursuing money and status because they see others pursing money and status. They may testify they are pursing these for some other end, such as bettering the world as a great lawyer, businessman, etc. But pressed, Girard found people don’t know why they desire what they desire, but can only provide as rationale that other people that desire the same thing.

As you might imagine, a bunch of people copying each other’s desires for the sake of it will inevitably lead to conflict. On the community level, Girard explains, this leads to the group singling out an individual who shares the desire and placing all the blame for the rising tensions on them.

Enter: the scapegoat.

Girard can show that essentially all of human history is founded upon this pattern: 1) the mimetic desire 2) identification of a scapegoat 3) murder of the scapegoat 4) subsequent and temporary peace 5) repeat.

All mythology, origin stories, or sagas of a society are founded on the scapegoat. For example, in the origin story of Rome, Romulus and his brother Remus are arguing over who should rule the city. Romulus kills Remus, sealing his belief in his own righteousness, and the city is named Rome. In prehistoric communities, tribes would settle their tensions by exiling or otherwise marking out an individual as the source of their troubles. Only by killing them in an ecstatic pitch would peace be restored. Asa final example, in religions based on a sacrificial rite, such as Judaism, the iniquities of the group were placed upon the sacrificial animal which, once killed and offered up to God, removed their guilt.

Thus, a pattern is irrevocably identified.

Throughout all human history, the scapegoat plays the part of settling the qualms of a desirous society and allowing them to progress and achieve those desires without destroying themselves. In the Christian context, this sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Might we be on the brink of simply explaining away the Christian story as a pattern that has existed since the beginning of time?

Inconveniently, no.

All previous and existing origin stories, mythologies, oral traditions, and religions follow the known scapegoat pattern, except for one: The story of the Christ.

In this one and only case, the iniquities of the society were not resolved by the scapegoat. Rather, history is insistent that Jesus was wholly innocent, the spotless lamb, and as such, his death uniquely and singularly pointed the finger back at the persecutors—that is, all of us—to recognize, examine, and reform our sinful way.

If it is true that all mankind is founded upon the bloody act of murdering the scapegoat, would not God come to earth precisely as one of these? And if it is true that humanity is prone to engage in the downward cycle of miming each other’s base desires, which results in deceit and violence and killing, would not the solution be a well-placed desire in God alone?

As far as I can tell, those “if” statements are true, and the consequences that follow have been delightfully unveiling themselves to me with each passing day. That these ideas are so militantly suppressed in our age seems, like Girard’s analysis of the Christ, to be the greatest conceivable endorsement of their truth.

Dear Matt what a perfect argument tounderstand GOD and really what you quote are some kind of understanding of such a men and women, that would not only change the world but even the universe. Such men and women help us to prove there must be God and a master planner. Its a long story and its a story of humans. I mean anyone can love Jesus as we know he was not an ordinary man. But if read his story, you would be inclined to understand story of GOD. But I dont agree with you that GOD has been fpre saken by the modern society. On the contary look at Music, look at Art and look at any expression of aesthetics that can cover some level of complexity in life, you would realise either they have read the Bible, met a woman or man of some higher standing who know the story of God really well, or they are just telling you an incripted message waiting for people like you to tell the meaning of abstractness and its origins. And yes the story starts from Men and Women of religion and their Gods. As an economist I am well aware that God simply deleted as a religious reference in science but if you try harder and as you mention yourself, science was actually started because of those religious men and women and their actions which they would attribute to understadning a creator. Now you man call it with different names. Anything you cant understand and can do good would have various definitions. Yes, in statistics, you may define prophet hood as standard error. Its the same concept. In Physics, you may try to understand theory of everything through God's particle. But tI do note that you are talking about common people who claim they are secular and adhere to no cultural boundaries and would lead to socalled 'sinful' lives. Well evanglical Church has done an amzing work on that. Yes, people make fun of other people and that always happen on media. But there is still a religious logic to it. You wont want to be that perfect man or woman as then really the test would start. People may still to amazing things, people may still give everything for good and people may still work on social norms that promote love and tolerance and enlightenment. But it was only Jesus who could claim a Prophethood. The message that you have amply discussed is something that is mission impossible for the most progressive societies where every one would matter and perfect equality while retaining perfect prosperity is achieved. Instead, for all the great bollywood stars and celebrities, in India you publish a megazine called Star Dust that write news and articles to suggest the perfect man and a woman on screen is just a very ordinary man.In Pakistan, even a military dictator like General Musharraf would encourage media to criticise him and print his cartoons. Yes the problem with Western society is that they can ridicule anyone. Though laws on Antisemeticism are strong. So Islam helps you to first establish that his Prophethood was something where the divine message and contact being completed. Therefore Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is the last prophet of God (Allah). And the holy Prophet of Isl;am witnessed the greatness of Jesus Christ. Therefore your disappointment is valid but to make a rule is to atleast respect our forefathers and esspecially the men of consequence. We in academia do it often without any religious references. For example we think Adam Smith is the father of modern Economics but I would still respect Karl Marx and work on economics that can be built on Profit making as well as mitigate exploitation of workers. Therefore, never feel ashamed if some one would ridicule some one because in most cases those public faces are quite a great men and women themselves. No one would ever ridicule some one from the past as Martin Luther King but only his friends who lived with him. Instead great American nation would some day and years after him would elect the first black President of America. Therefore I agree with you for what wisdom you qoute and if this wisdom represents religion and men and women of God, then I would never disrespect any one of those times. But ridiculing a friend in 21st century is a fine sense of humour if its not directed towards any aspect of human misery. Yes you dont ridicule African Americans for being slaves but yes you would thoroughly enjoy the rap music of snoop dog. Who would call himself a snoop dog. For that you have to know the modern world of 21st century. Similarly there are so many examples that tell you that we are people of comfort and can afford humor. Kindly go and find if Jesus Christ has ever used Humor because his and his deciples were just too perfecr even for a scientific world that is being build today. It seems it was all a very very serious business that was about life and death. Only the bravest might have used even humor. That would change the modern world. Start from respecting people, not ridiculing anyone for any short coming and inferiority and be as humorous as possible. As a Muslim all Prophets of GOD should be respected as religion does appear to be a serious deal. Ypu must have heard about Mullahs in Pakistan and how repressive they are becuase they are always very serious esspecially during Afghan Jehad. Well I came back to Pakistan after 2009, and I must say if its about subtle humor, no one can match a pakistani Mullah but frist you need to understand the culture and a Pakistani Mullah would never disrespect anyone. Not even the enemy of Islam. But yes they might use some expressions that intend to make some kind of a fun of leaders like George Bush who would initiate a War on terror leading to just too many civilian casualties in countries like Iraq. Humor and promoting humor that is not disrespectful (I hope you understand the definition) is the essence of 21st century and practiced by every country of cosequence. After all, people would then know who were the great men and women of the past. It is indeed some one like Jesus. Therefore I hope I have explained how great is the modern world and you rightly pointed out where they have faltered leading to loss of human values.