Skull

Meditations on buying a skull.

No. 30: Skull

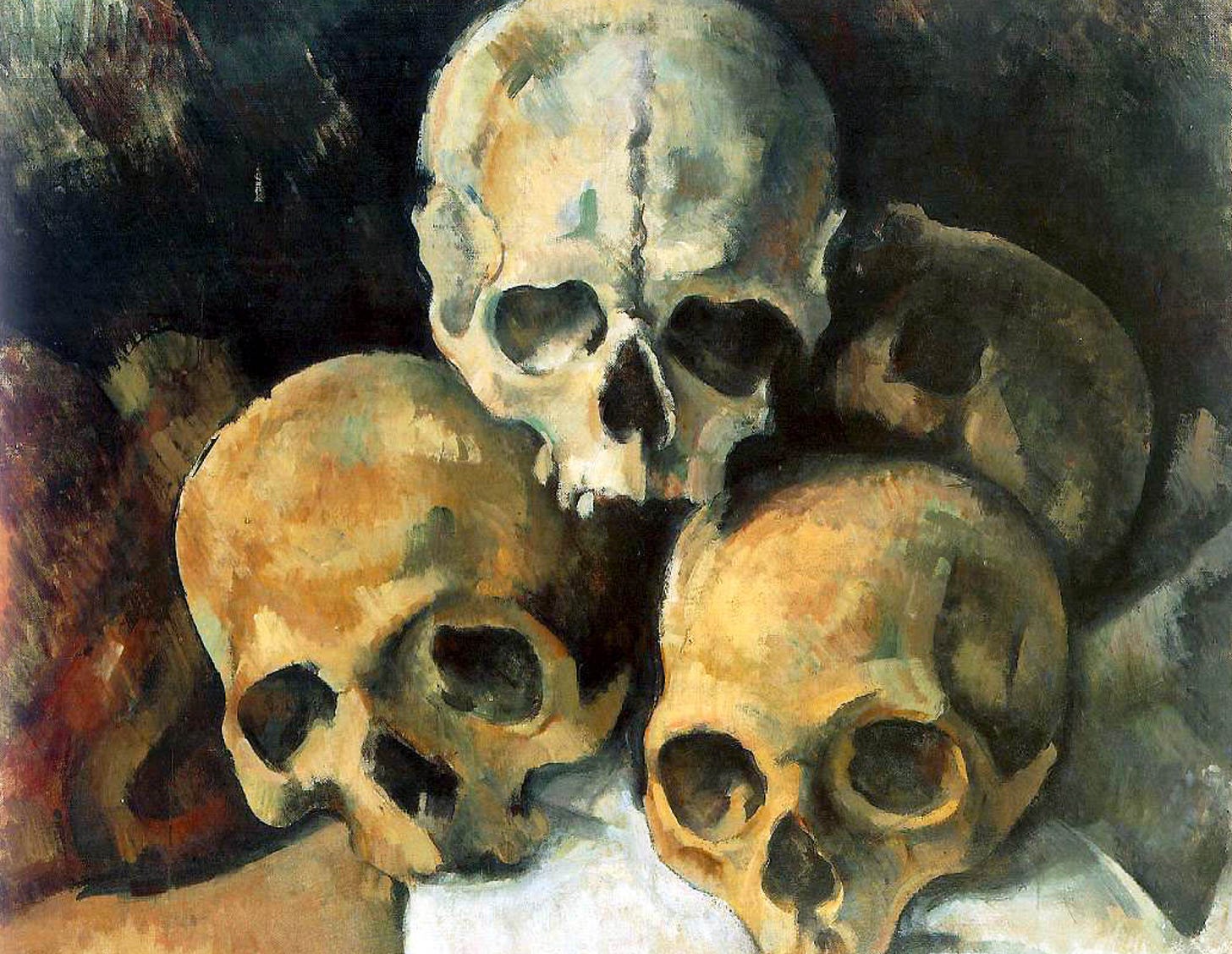

I bought a skull on Amazon this week. It felt like something that needed to be done in the name of art or momento mori or maybe I was just feeling lonely. Great people have enjoyed the company of skulls long before me, so I figured what the hell, Buy now. Take Van Gogh, who used a skull to paint a skeleton smoking a cigarette. (My skull’s a non-smoker.) There’s Cézanne, who piled four skulls on top of each other and named the painting “Pyramid of Skulls.” (As of now my skull has no fellows, that I know of.) David Sedaris acquired a skull in Paris. It came with its own skeleton and it talks, saying things like “You are going to be dead . . . someday.” (So far mine’s mute and I’m OK with that.)

Thanks to those artists, skulls had been floating around in my skull. But I felt no need to purchase my very own until I read James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man last week. It wasn’t a wonderfully poetic passage that pushed me over the edge, but a simple description.

He saw the rector sitting at his desk writing. There was a skull on the desk and a strange solemn smell in the room like the old leather of chairs.

Your order’s in!

After placing the order, I stopped thinking of skulls and continued reading the coming-of-age story of Stephen Dedalus, that Irish kid who grows in phases towards his final form: the artist. Unlike wild things that humbly grow without questioning their place in the order, Stephen’s breakthroughs are grueling ordeals like that of a caterpillar forced into chrysalis too soon and released as a butterfly too late.

Young, melancholy and top heavy with the teachings of the Jesuit Catholics, he lets desire take him down flagstone streets where the hand of a woman in a pink gown lands on his forearm. The words “Good night, Willie dear!” (1914 Ireland for “Hey, baby”) and he’s led to a typically sparse room: bed, nightstand, lamp.

She undresses and holds him to her. Out of joy and out of pent-up everything he weeps hysterically. The the next night he weeps less. And the next night he’s a natural. And so he defiles himself before his God.

Then the rector of the college announces a retreat focusing on the four “last things”: catechism, death, judgement, hell and heaven.

“And if, as may so happen, there be at this moment in these benches any poor soul who has had the unutterable misfortune to lose God’s holy grace and to fall into grievous sin I fervently trust and pray that this retreat may be the turningpoint in the life of that soul.”

Less than ideal timing for Stephen.

Over the course of the retreat the rector harps on the tortures of hell and the folly of the sinner. Hell is described in detail: it’s nothingness of interior and exterior darkness, the burn of everlasting fire, the sickening stench of millions upon millions of fetid carcasses decomposing and massed together in a reeking mass, one huge and rotting human fungus.

Stephen felt all of it was for him. As I laid on the grass near Lake Merritt reading and being battered by punches of strong wind, I felt all of it was for me, too. These apparently bespoke addresses cast Stephen into dread and me into a lesser dread. What cut us (Stephen and I) especially deep was the rector’s description of the intensity of the spiritual, not physical, pain one can expect to meet in hell. Knowledge there is used against you. Unfortunately for your future damned self, you’re allowed lucidity in hell.

“You had time and opportunity to repent and would not,” the rector says to the hypothetically already-damned and rotting souls of the boys that fill the pews. Their faces are pale. “And now, though you were to flood all hell with your tears if you could still weep, all that sea of repentance would not gain for you what a single tear of true repentance shed during your mortal life would have gained for you. You implore now for a moment of earthly life wherein to repent: in vain. That time is gone: gone for ever.”

I shut the book. The winds had gotten stronger and I was cold and in need of food. I started making my way up the hill to my apartment. My parents raised me Catholic. I was baptized, made my first communion, completed the sacrament of confirmation. I was Stephen, in many ways, and if my religious teachings were multiplied a millionfold I would have been Stephen actually, Stephen who had nightmares of goats with human faces and could hardly walk and vomited after the priest’s words registered with shrill, unequivocal doom.

Why was I not afraid like him? Had I doubted? Yes.

Do I doubt? Yes.

Do I condemn everything having to do with structured religion? No.

Stephen was sixteen during the retreat and much more pious than me at that age. After my confirmation, I went the way of the modern intellectual, or so I thought. That is, condemnation of the christian ideal. I was sixteen. Clearly, I was the smartest man in the world.

To most midtwenties religion is a frightening subject breeding hotheads and lofty ideals and sudden philosophers. Their sights are usually aimed at the thousands of atrocities committed by the church, and rightly so. That, and dinosaurs. But isn’t every atrocity, the very institution of the church, the bible (which includes the dinosaur thing) man-made, done-by-man, man-influenced, man-written or manned by men who are not God despite their claims of being something close to the real thing?

In the same way it’s impossible to prove God, it’s impossible to disprove God. This renders all arguments piles of ash until we’re back to square one: belief. Given the choice to believe in something or to believe in nothing, I began to wonder if perhaps I’d rather believe in something. Plus if the rector is right about all he said about hell, about sin, about repentance, and if God approves of this theology, and if right now, on my walk back to my apartment, I’m hit by a car and killed, then . . .

then . . .

. . . down, down to the foul-smelling place I go.

I reached my building, climbed the stairs, and found at the foot of my door the skull, still packaged, awaiting me.

I pulled the head out of its box and felt an urge to name it — to call it “him” or “her” instead of “it,” but so far I’ve refused the urge on some principle: domestication or pet-making of something as big and looming as death or something like that.

In a chapel across town, Stephen repented for his promiscuity, not daring to give confession at the same church where the retreat was being held. He was absolved, and for the rest of his time at Clongowes college he lived piously, monkwise, and felt the serene kind of relief that comes from avoiding certain agony. In his last year, the rector called Stephen up to his chamber, the one where the skull lives, and invited him to join the priesthood.

He had often dreamt of becoming a priest, but the horror of his nearfall from grace had within it a profoundness rarer than the sterile life the priesthood could offer. In that twisted glee of falling, of landing in the mud, in cleaning himself and being born again he discovered something in him that was there all the time: a blinding light that can’t be contained or snuffed or diminished regardless of anything, a light that was was brightest when free from shades that would shape its rays this way or that.

“The snares of the world were its ways of sin,” the narrator writes. “He would fall. He had not yet fallen but he would fall silently, in an instant. Not to fall was too hard, too hard: and he felt the silent lapse of his soul, as it would be at some time to come, falling, falling but not yet fallen, still unfallen but about to fall.”

Former classmates who decided to join the brotherhood pass by.

Brother Hickey.

Brother Quaid.

Brother MacArdle.

Brother Keogh.

Stephen considers: “Their piety would be like their names, like their faces, like their clothes, and it was idle for him to tell himself that their humble and contrite hearts, it might be, paid a far richer tribute of devotion than his had ever been, a gift tenfold more acceptable than his elaborate adoration.”

Elaborate adoration. This is how artists are made. ⧫