This post, according to Substack, is “too long for email,” not because of the amount of writing, but because I included a bunch of photos. Please tap the headline of this newsletter to read it—and view the photos within—on my website. Love, MZ

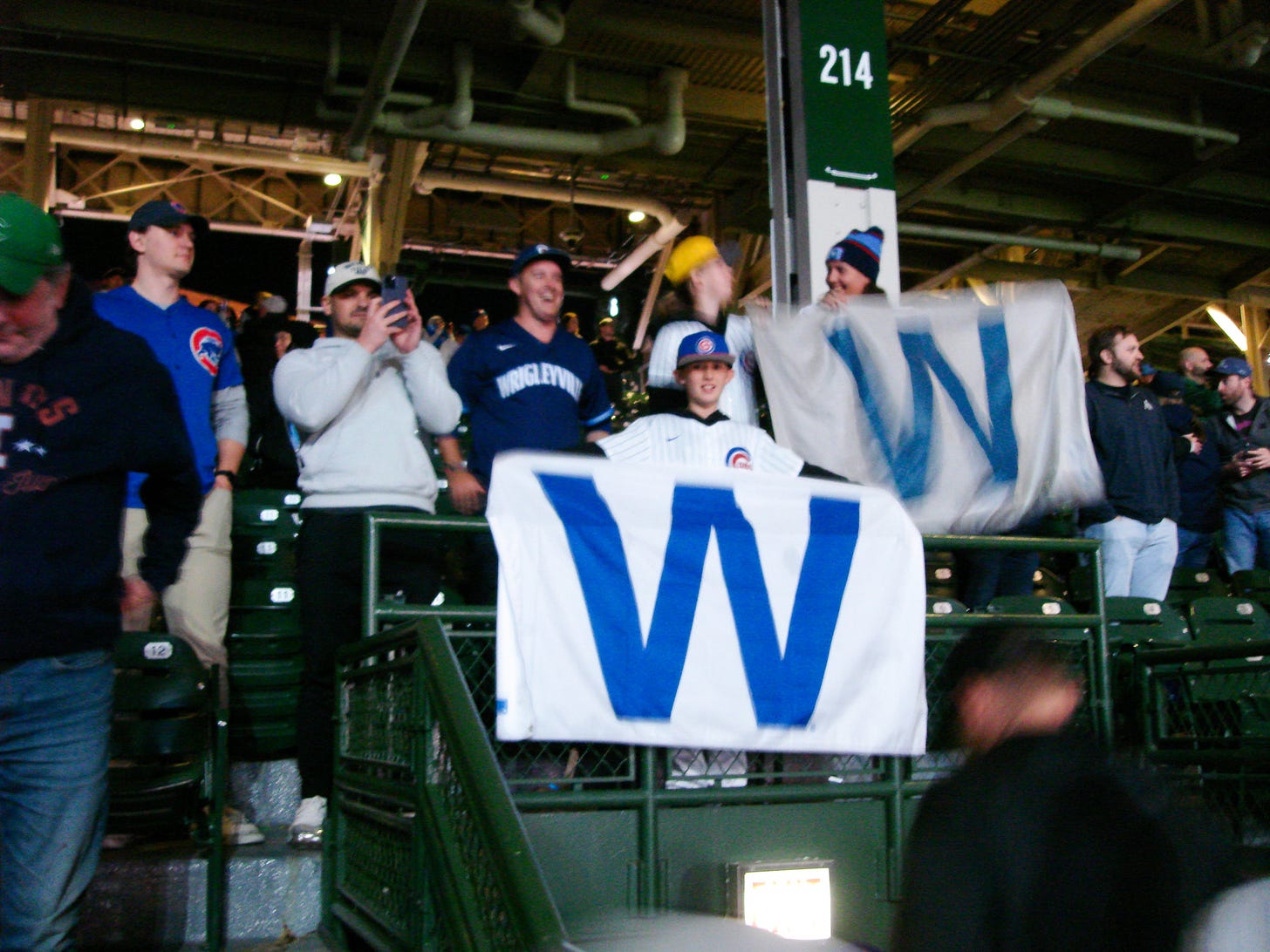

Photo Essay No. 4: Things I saw at Wrigley Field

I heard something the other day I liked: the idea of life as a game (especially as we tend to know them in the professional sphere i.e. MLB, NHL, NFL, etc.) and the idea of a game not as a high-stakes matter of winning and losing, but as a celebration, one in which all are invited as celebrants, though participation is ultimately a choice.

The “game” concept of life is nothing new. It suggests each of us are players, that the clock starts when we’re born, and the buzzer sounds when we go. The surface-level takeaway is that in life we should play hard, score as many points as possible, and most importantly, win.

But to such ideas, let’s toss up a challenge flag.

If the winning and losing aspect of a game is less an end but the means of participating in the celebration, the phenomenon of players, fans, officials, announcers, and the rest coming together to be joyful — to, in short, play — makes much more sense.

After all, for all the hype, seriousness, and money-making associated with sport, it’s really just bunch of people dressing up in colors to do something essentially pointless, and thus pure, for the fun of it. A given sport is play inasmuch as kids playing “house” is play. Sports are entirely made up. Points are imaginary. There’s a shiny trophy to be had at the end of each season, confetti to be dropped, names to be added to Halls of Fame. And what — or whom — is that trophy really for? When the victors raise the golden cup over their heads, can we be so naive to think this piece of metal was the true goal? That the happiness and cheer is felt by those who played on the field alone?

Fans follow a team because it’s fun. As for players, despite their fat paychecks, none achieves professional status without an unadulterated love for the game and a lifetime spent playing pay-free. To win or to lose in sports changes nothing about reality or people, but rather celebrates both reality and people. By fabricating made-up rules, boundaries, and outcomes, we make playtime more playful. The upshot? Even in a wide and expansive universe — or perhaps because of its wideness and expansiveness — there are better, more organized, and more focused ways to celebrate life than simply wandering around, hither thither. A celebration, by definition, requires a collective cause or reason. A game is that. In the aforementioned analogy, life is also that. But again, only for those who chose to participate.

Take a baseball game at Wrigley Field like the one I attended recently with my friend Victor. If we step back from all the preconceived notions surrounding sports (not that this is a requirement to enjoy a given sport, but for the purpose of this essay, it is) the whole is a sight to see. Thousands of people emerge from their dwellings to come together in a massive, man-made arena. There is music, singing, food and drink. A perfectly-groomed field spreads out before the crowd. Players emerge in colorful uniforms and begin to toss a ball around. Finally, the game begins. Points are earned. A winner emerges. Cheers erupt. All go home.

For what?

On the one hand, the celebration of life and aliveness we’ve talked about. On the other, for the hell of it. As previously discussed in this newsletter, those “wastes of time” are surely the holiest of all. Thus, the game as analogy for life works differently than the traditional win-loss paradigm. To rightly participate in “the game” we must first recognize our relationship to others, coming together to either participate or spectate but most importantly to fix joyful attention on the act of play. As players too, we must care for ourselves not in order to win, per se, but to perform well enough to be an active celebrant. Also as players, we must have a goal in mind, whether it’s to run fast, hit far, shoot straight. To score a goal, a run, a touchdown; to hit the bullseye, the field goal, three-pointer: this is to rightly be — which isn’t to say we’ll make every shot, but that our desire is calibrated correctly. It would be odd for a player to repeatedly send the ball out-of-bounds, either intentionally or out of carelessness.

We could continue with the particularities of the analogy, but I think the main takeaway is this: to play the game of life is just that — to play, to celebrate, to make good attempts at 1) understanding yourself not as an individual, but as one in the context of many 2) fulfilling your potential as part of the whole 3) celebrating those who are fulfilling their potential exceptionally well, and learning from them and honoring them. Again, the thing is play; the thing is the pointlessness; the thing is the weirdly radical idea that, perhaps, the best thing we can do in life is behave like a professional athlete: always attempting to stay fit, to make the best play, to help the team, and to have loads of fun doing it.

Finally, and paradoxically, it seems that it’s within the man-made bounds of the game or the organized celebration that we are in fact the most free. This challenges the modern notion of freedom, which implies that absence of rules is true freedom. Perhaps instead it’s running onto an open field knowing the rules of the game, then seeking to make the most of them, when we’re able achieve the most. True freedom, in this case, is found when we’ve all come together within an agreed-upon space to play, rather than wandering around individually, which tends to manifest more like lostness.

Anyway, it’s something to think about. There’s a beauty to sports — to the game, to the field, to the crowd — that reflects life in general, I think, and maybe it’s that elusive but perceivable aspect of celebration that underlies every sporting event. In the same way a win is accepted as a win, a loss as a loss, perhaps we could all be less critical about the various ways our lives fail to cater to our supposed needs, and spend more time instead celebrating the good things we have, like our health, a summer night, an 6:20PM start between the Chicago Cubs and the Houston Astros at historic Wrigley Field.