This post, according to Substack, is “too long for email,” not because of the amount of writing, but because I included a bunch of photos. Please tap the headline of this newsletter to read it—and view the photos within—on my website. Love, MZ

Photo Essay No. 3: Things I saw on St. Patrick’s day

Long time, no see, dear readers. I hope all is as well with you as it is with me—that your life is good, or at least peaceful, and if neither of those, that it’s at least trending towards goodness or peace.

If not?

In the midst of even the greatest tragedies, it seems peace is available to those who hope for better days and commit to the work involved in finding them. Despair, on the other hand, is a downward spiral forever and ever and ever.

But philosophy and metaphysics aren’t what I planned to share. At least, not today.

Last weekend, my fiancé Grace and I ventured to explore Chicago’s drunkest hour, St. Patrick’s day. Armed with my small but trusty Sony Cybershot camera, I snapped some photos of the event. Thus, let this ‘photo essay’ commence.

While St. Patrick’s day is by no means defined by the way in which people celebrate it, it does seem that, on the whole, it’s a day dedicated to drinking copious amounts of alcohol from the break of day until late-night collapse.

This is in keeping with what a certain religious figure has called our modern “culture of death,” which I like to mentally revise to “cult of death” for added effect.

I’ve been thinking about this concept a lot recently, reflecting on my past choices and the mainstream behaviors of the American citizenry I love to observe from behind the dark lenses of my sunglasses.

The “cult of death” concept does, in fact, seem to check-out.

The culture accepted as normal today displays a certain amount of hopelessness, isolation, and unhealthiness a.k.a. a preference for choices that trend slowly but surely toward something less than a life fully lived, both spiritually and biologically.

I wonder: Why?

Only consider the acts of most teenagers and college kids, or of yourself at those ages. Consider the acts of adults, and the material ways many pursue happiness and pleasure. Consider politics, and the way people tend to treat each other. Consider, in general, the attitudes and choices considered acceptable and mainstream today, and whether they are life-giving, or not.

This isn’t an observation made out of condemnation, but out of love. Neither is this an observation made out of abstinent asceticism, but out of skepticism of a purely material world. This is not an observation made from on high, but from the vantage point of one who has actively tossed and turned through 29 years of life—and in many ways, still is—making choices both good and bad in the name of meaning.

(I lied earlier. I guess philosophy and metaphysics is what I’m going to talk about today.)

Life involves so many indulgences. That’s a good thing. We should soak them up as an end in and of themselves, the same way we dance for the sake of dancing. The sad note only sounds when indulgences are a means to an end—the final option for people seeking relief—or the perceived natural way of life: that everything that has been, is now, and will ever be lies in the materia, and that the game is to accumulate as many tangible things and experiences as possible before we expire.

This boils down, I think, to our feeling lost. We reach out and grab apparent happiness and apparent pleasure where and when we can from the things we can see and feel, and again and again these turn to dust, and we are left to begin again.

These meandering thoughts are not aimed at the happy people of Chicago simply enjoying a holiday, but they are, in part, inspired by them.

As we adventured through the crowds and passed by high-schoolers carrying milk jugs of liquor, I couldn’t help but note the fundamental, and fun, paradox of this being the feast day of a literal priest, a saint, a man who, according to the church, is one of heaven’s elect.

I wonder how St. Patrick would react to the popularity of his feast day as it stands today. Would he chuckle at the wildness of it all, smiling at the people coming together, without entirely condoning the underlying theme of getting as f*cked up as possible as efficiently as possible? Would he be disgusted? Would he be melancholy, regretting to see his beloved brothers and sisters thrashing their bodies in his name?

Who can say? But it does prompt a question that extends beyond St. Patrick and his feast day: Why do we love to dull ourselves? Why do we constantly put ourselves in situations more painful, ultimately, than need be? Why has this been the lot of humans since the beginning of time, to deliberately trip ourselves up with excess, anger, selfishness, jealousy, desire, and the rest of those ‘deadly sins’ which, if pleasurable at first, predictably lead us to some sorry state?

Correct or not, my theory is simple

We struggle immensely to love ourselves.

We struggle to concede the idea that we deserve not only better, but best.

We struggle to fill-out our true dignity as unique persons, the dignity a loving parent can’t help but see in the immaculate purity of their growing child.

With this, we congregate with others who share the same struggles, forming the so-called “cult of death,” a cult that actively opposes the equally viable potential for a “culture of life,” the tenants of which direct us to think less about ourselves and instead about each other, and in the process—paradoxically—to find ourselves.

How beautiful, then, is the practice of art, of photography? Only a year ago, I probably also viewed St. Patrick’s day—as well as many other days—as a good opportunity to get radically intoxicated. But this time, Grace and I set out with the object of capturing the day, and sharing it, with our cameras.

In other words, the aim of the day had was centered not on ourselves, but on the other.

All good art, as a rule, works this way. It’s an act of love, which is an act of selflessness. It’s a gift that can only be given and received in gift-form, or, as yet another figure has said, it’s proof that “our being increases in the measure that we give it away.”

I don’t think the “cult of death” that exists today is a matter of people actually being lost, but rather our being too focused on ourselves and our “lostness”. What if, instead, we focus on how we might contribute to someone else’s life? Or what if we focus on the thousands of ways in which we’ve benefited from—and, in fact, exist because of—the gifts of others? It seems, in either case—and especially in both—lostness dissipates, if only because there is nothing to be “lost” anymore, only one who exists because of the gifts of others and for the benefit of others.

For all my chatter, after a couple of hours of wandering through the festivities I popped into a Walgreens to buy a 20oz Sierra Nevada.

It wasn’t yet noon. It was delicious.

I wanted to crack one for old St. Pat, that saint who planted the seeds of his teachings in pagan Ireland. A feast day does after all a call for a feast, which generally involves both food and drink.

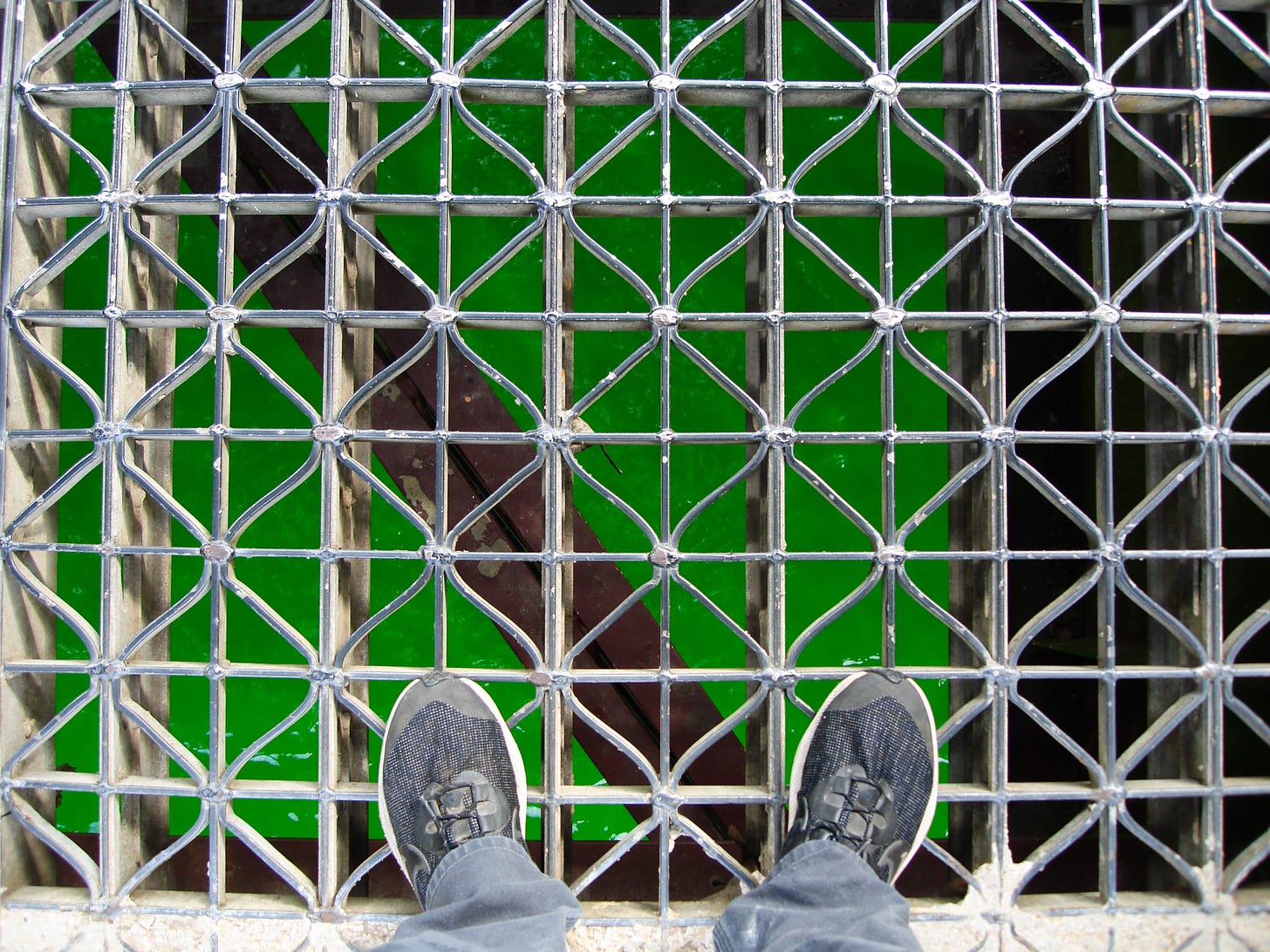

For all its debauchery, St. Patrick’s day in Chicago is something special. We dye our river the color of industrial-grade laundry detergent, bid the creatures who call the water home good luck, and proceed with our celebrations. Joy truly abounds. It made me happy to see so many people in one place, so jubilant, so carefree, and to be one among them.

If only in rare moments, you can’t help but lose yourself in the spectacle of it all. This temporary ego-death is something St. Patrick would be glad to attribute to his name, I’m sure.

Great to see you, Matt!

You’re back! Glad you got a drink before noon